Fear and anxiety are among the most pervasive emotions in human life. In contemporary society, anxiety has almost become a collective condition. The pressures of modern living, constant connectivity, and exposure to uncertainty have left many people existing in a low-level state of alarm. This has deep psychological and physiological consequences, shaping how we think, relate, and behave.

“Where there is other, there is fear.”

Upanishads

Spiritual and transpersonal traditions, both ancient and modern, invite us to look deeper. They ask whether fear is an inevitable part of human existence or a misunderstanding of who and what we really are. The teachings of the Upanishads and the insight of teachers such as Nisargadatta Maharaj suggest that the lasting freedom from fear is not in controlling circumstances but in transforming perception itself.

Listen to this blog…

The Nature of Fear and Anxiety

Fear is a response to a specific, immediate threat. It activates the body’s defence systems, triggering the fight, flight or freeze reaction. From an evolutionary point of view, fear helped our ancestors survive real dangers.

Anxiety is different. It usually concerns what might happen rather than what is happening. It is sustained by imagination, memory, and anticipation. Modern neuroscience shows that the same neural pathways involved in fear also fire during anxiety, but the trigger is often cognitive rather than external. The body prepares for danger that may never come, and over time this becomes habitual.

In psychological terms, anxiety develops when the nervous system remains in a state of hyperarousal. It is as if the body no longer trusts the world to be safe. The question that both psychologists and spiritual teachers explore is how to restore that sense of safety, not just mentally but existentially.

The Upanishadic Principle: When There Is Other, There Is Fear

The Upanishads articulate a profound principle: “Where there is other, there is fear.” This does not refer merely to the fear of physical danger but to existential fear — the anxiety that arises when the mind sees itself as separate from the totality of life. When we perceive ourselves as isolated, surrounded by forces we cannot control, fear naturally follows.

In this view, fear is not something to be conquered; it is to be understood. The texts point to non-duality, the realisation that the boundaries between self and world are ultimately conceptual. When one sees the unity behind multiplicity, fear dissolves, not because circumstances change, but because the perception that created separation is no longer dominant.

The Upanishads propose a contemplative approach rather than a technique. Practices such as neti, neti (“not this, not that”) guide the seeker to recognise what is transient and not truly self. Through this inquiry, one arrives at the unchanging awareness behind all experience. In that awareness, there is no “other,” and therefore, no fear.

Insights from Nisargadatta Maharaj

Nisargadatta Maharaj, a twentieth-century sage from Mumbai, expressed this truth with striking directness. He often said that every human being lives between two poles: fear and desire. Fear emerges from the sense of insecurity, while desire arises from the feeling of incompleteness. Both depend on the assumption that one is a finite being trying to manage a vast and uncertain world.

His central instruction is remarkably simple: remain with the sense of being, the feeling “I am,” without adding any descriptions or stories. This awareness is prior to thought and identity and beyond time and space. Over time, remaining with this sense of transpersonal presence reveals its spacious, stable nature. When this is deeply recognised, fear loses its foundation because there is an unshakable knowing of wholeness.

Nisargadatta insisted that such recognition can bring about an irreversible, permanent shift. It is not an altered state to be gained or lost but a realisation of what has always been the case. Once this understanding stabilises, daily life continues, but the background of anxiety disappears. One is no longer reacting to imagined threats but responding to reality as it unfolds.

Parallels in Other Traditions

The experience of such a shift appears in many spiritual lineages. Zen Buddhism speaks of kenshō or satori, moments of seeing one’s true nature beyond conceptual thought. Advaita Vedanta describes the same recognition as self-realisation. Sufism speaks of fana, the dissolving of separateness, followed by baqa, abiding in divine unity.

Although the languages differ, they converge on a single insight: when one recognises the whole as oneself, the habitual reactions of fear and grasping naturally cease.

The Psychological Parallel: From Reactivity to Regulation

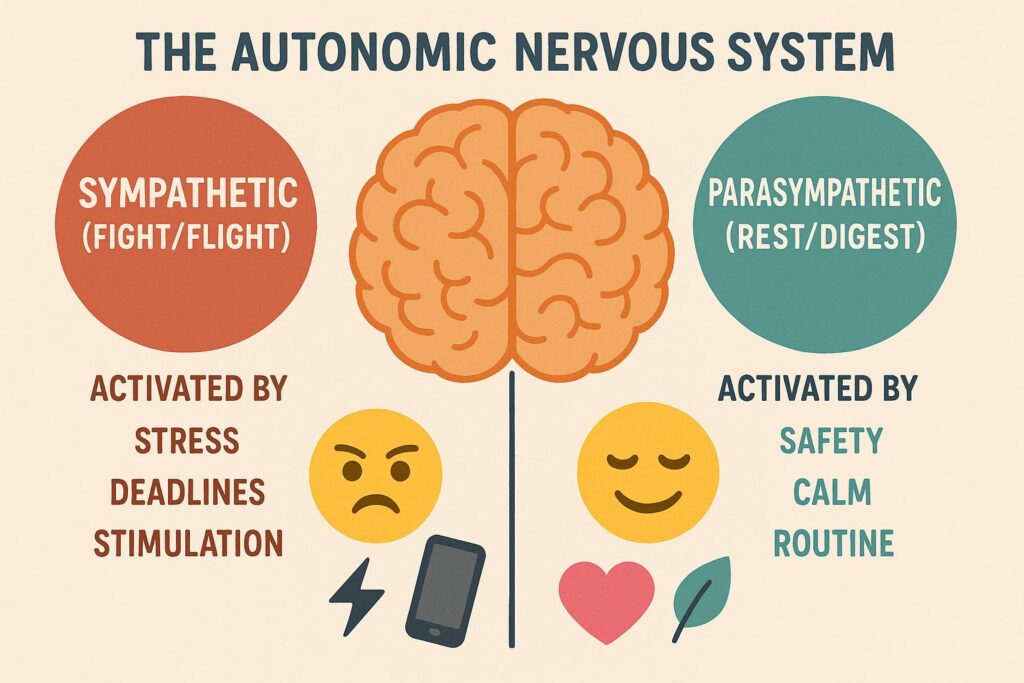

Modern psychology and neuroscience provide a complementary understanding of this transformation. The nervous system operates in states of defence or safety. When a person perceives threat, the sympathetic nervous system activates, increasing heart rate and alertness. When one feels connected and safe, the parasympathetic system predominates, promoting calm and healing.

Practices that evoke non-dual awareness, such as mindfulness, breath awareness, and self-inquiry, regulate the nervous system. By returning attention to the present moment and relaxing identification with thought, these practices quiet the amygdala (the brain’s fear centre) and increase activity in regions associated with empathy, compassion, and emotion regulation.

Thus, both neuroscience and the Upanishadic teaching converge: fear recedes when the sense of separateness softens and awareness returns to wholeness.

Body First, Mind Second: Why Physiology Matters for Fear and Healing

William Bloom’s article “Polyvagal Theory & Emotions” argues that while talk therapy can be valuable, deep emotional pain often responds more effectively when approached through the body rather than through the intellect alone. Drawing on Candace Pert’s work on neuropeptides and Steven Porges’ polyvagal theory, he explains that moods and emotions are biochemical states and that our nervous system cycles through three core modes: safe and social, threatened and mobilised to fight or flee, and traumatised and immobile. These states shape how we feel and think long before conscious reasoning gets involved.

Bloom then proposes a “Fourth State”: the capacity of the evolved human brain to step back and witness these bodily and emotional states, rather than being submerged in them. Through practices such as mindfulness and meditation, this witnessing awareness can learn to observe and skilfully influence the “stew” of hormones and nervous system reactions, integrating body and mind in a more compassionate, conscious way. His piece reinforces the idea that freedom from fear is not achieved by thought alone; it requires engaging with the body’s physiology and then cultivating a reflective, witnessing presence that can hold and transform these fear states in real time. Bloom, W. (2019, December 27). Polyvagal theory & emotions. https://williambloom.com/2019/12/27/body-first-mind-second

Inner Conflict: When “Parts” Become “Others”

Inner conflict often feels like an argument inside the mind, with different parts of oneself pulling in opposite directions. Contemporary “parts” approaches in psychology, such as Internal Family Systems and related models, suggest that these subpersonalities each carry their own needs, fears, and protective strategies. When one part wants safety and another craves risk, or one seeks intimacy while another pushes people away, this multiplicity can feel as if there are many “others” living inside. In the light of the “no fear” theme, these divided inner parts can indeed function as “others,” generating turmoil, anxiety, and self‑sabotage.

Voice Dialogue, developed by Hal and Sidra Stone, offers a practical way to meet these inner voices by giving each part literal “voice” and space, usually by moving between chairs or positions as different selves speak in turn. This process brings unconscious dynamics into awareness and helps a witnessing consciousness emerge that can listen to all parts without being dominated by any single one. Building on this, Genpo Roshi’s Big Mind process integrates Voice Dialogue with Zen, using the same “giving voice” method to access not only everyday subpersonalities but also a more expansive perspective or transpersonal Self he calls Big Mind, a direct taste of spacious, non‑dual awareness. In this sense, inner conflicts are not eliminated by suppressing difficult parts, but by including and integrating them within a larger field of awareness. When the many internal “others” are held within Big Mind, they lose their threatening quality and become expressions of one underlying wholeness, allowing fear to soften into understanding.

Meditation may not be for everyone.

Beyond Karma Yet Grounded in Reality

An enlightened person is often described as being beyond karma because their actions no longer arise from personal desire, fear, or attachment. Karma is understood here as the natural law of cause and effect, where every action generates corresponding outcomes in thought, behaviour, or circumstance. In such a state, there is no psychological residue to create future consequences; actions flow naturally from clarity rather than conditioning. This freedom from inner conflict is why fear no longer finds ground, and the habitual patterns of cause and effect lose their binding strength. Although an enlightened person is beyond karma, he or she does not ignore karma. They remain fully aware that the natural order of the world continues, where actions still have tangible consequences and the laws of cause and effect still operate. What changes is the relationship to those events: life is lived with understanding, equanimity, and compassion, without the distortion of fear or anxiety.

Living in the State of No Fear

To live without fear is not to become passive or naïve about danger. It is to perceive from a deeper stability that cannot be shaken by circumstances. This stability is not built through control but through understanding.

When one rests in that awareness, life continues with its natural challenges, but fear no longer defines perception. The body remains alert and responsive, yet the mind is no longer trapped in anxiety about the future. This state is not achieved through effort or suppression but through direct insight into reality as it is.

Ultimately, the promise of no fear lies not in escaping vulnerability but in recognising that our awareness itself is never threatened. When that recognition becomes steady, as Nisargadatta said, it is an irreversible shift. What remains is simplicity, clarity, and peace — a life lived in the light of unity rather than the shadow of fear.

Reflective and Practical Guidance

1. Sit in Presence Each Day. Spend a few minutes each morning sitting quietly, feeling the natural rhythm of breathing. Let thoughts come and go without judging them – like watching clouds pass by. Notice the simple sense of being — the awareness in which everything appears.

2. Observe Fear Without Resistance. When fear or anxiety arises, instead of trying to suppress or analyse it, notice its physical sensations. Feel where it lives in the body. Allow it to be present without reacting. This acceptance begins to dissolve its control.

3. Reconnect through Gratitude and Nature. Step outside daily, even briefly, and sense the continuity between your breath and the living world. Gratitude grounds awareness in connection rather than isolation. Ground yourself in nature (walk barefoot where possible or have a bath with Epsom/magnesium salts).

4. Reflect Before Sleep. Each evening, recall moments of reactivity during the day and imagine how they might have been met from calm awareness. This gentle self‑observation plants the seed for transformation.

5. Remember: You Belong. Beyond all changing circumstances, attend to the underlying wholeness of life and existence. The recognition of this unity is not mystical escapism; it is the beginning of freedom from fear or anxiety.

Reflective Journal and Meditation Prompts

1. Exploring Fear and Separation

When you feel anxious or afraid, pause and ask: “What am I imagining will happen?” and “Who is the one that feels threatened?” Notice whether the fear is about a real event or an imagined future. Gently trace the feeling to its root — does it arise from a sense of being separate or unsupported?

2. Recognising Wholeness in Ordinary Moments

Take a few minutes each day to notice moments when you feel connected — to another person, to nature, or to stillness or something else that works for you. Reflect on how fear diminishes when this sense of connection deepens. Write down a few lines about what that felt like and what helped it appear.

3. Seeing Cause and Effect Clearly

At the end of the day, review one action or choice you made and observe its immediate consequence, whether internal or external. This cultivates awareness of karma in the practical sense, reminding you that understanding and responsibility are parts of freedom.

4. Shifting from Reactivity to Presence

Reflect on one recurring situation that usually triggers anxiety or defensiveness. How might it change if you approached it from calm awareness rather than automatic reaction? Visualise yourself responding from steadiness, observing the difference in tone and outcome.

5. Contemplating the Question “Who Am I?”

Sit quietly and repeat inwardly, “Who am I, before thought, before emotion?” Stay with the question without seeking an answer from the intellect. Let awareness itself reveal the stillness beneath experience, the space where fear cannot find ground.

These reflections encourage direct observation rather than analysis. Over time, they nurture insight, transforming fear into understanding and restoring trust in life’s natural balance.

A Friendly Universe and a Safer World

Albert Einstein is widely credited with saying that the most important decision we make is whether we believe we live in a friendly or a hostile universe. This question goes to the heart of fear and trust. If the world is seen as fundamentally hostile, the nervous system remains on permanent alert, and fear becomes the default lens. If it is seen as at least fundamentally trustworthy, the possibility of relaxation, cooperation, and creativity opens.

From a non‑dual perspective, the universe is not separate from what we are; it is the field in which experience arises. This does not deny that painful or harmful events occur, but it reframes them within a larger context of meaning, growth, and interconnection. A “safer world” is not one in which nothing difficult ever happens, but one in which more people relate to life from trust rather than chronic fear. In that sense, each person’s inner work contributes to collective safety: every time fear is met with understanding rather than aggression, the world becomes marginally less hostile and more aligned with the “friendly universe” Einstein invited us to consider.

To sum up, this integrated understanding — where psychology meets philosophy, and ancient insight meets modern science — reveals that fear and anxiety cannot survive in the light of awareness, awareness of ‘no-other’. Living in that light is the true state of no fear.

Paul McCartney was seen walking barefoot on Abbey Road in London back in 1969, promoting grounding to counter his smoking habit.

Questions & Answers

Is anxiety just a medical issue, or can it be seen spiritually as well?

Anxiety can be understood both medically and spiritually. Medically, it involves heightened arousal in the nervous system and patterns of worry that can be treated with psychological and physiological tools. Spiritually, anxiety can be seen as a symptom of feeling separate, disconnected, or unsupported by life, which non-dual teachings address by pointing back to an underlying unity and safety that is not dependent on circumstances.

How is fear different from anxiety in this context?

Fear is usually a response to an immediate, identifiable threat, while anxiety tends to be diffuse, future-oriented, and often focused on possibilities rather than actual events. In the blog, fear is treated as a basic survival response, whereas anxiety is framed as fear extended through imagination, continually fuelled by the sense of separation and uncertainty.

What does “where there is other, there is fear” really mean in everyday life?

This Upanishadic insight suggests that as long as we experience ourselves as fundamentally separate from others, the world, or the ground of being, fear will arise because “the other” can appear threatening. In everyday life this shows up as constant vigilance, comparison, defensiveness, and the feeling of being alone against the world; non-dual practice invites a shift into seeing oneself as part of a larger whole, which naturally reduces fear.

Does non-duality mean ignoring real problems or injustice?

No. Non-duality is not a bypass of reality but a change in the way reality is perceived and responded to. Recognising a deeper unity does not deny pain, injustice, or harm; rather, it can foster clearer, less fearful action because responses are not driven solely by defensive reactivity. The blog’s section on karma emphasises that even if one is inwardly free, one still honours the law of cause and effect in the physical and social world.

How does polyvagal theory support the idea of “no fear”?

Polyvagal theory shows that feelings of safety or threat are closely tied to autonomic states in the nervous system, which shape emotions and thoughts. Practices that evoke calm and connection, such as slow breathing, mindful awareness, and compassionate presence, help shift the body from defensive states into safety, which aligns with spiritual teachings that say fear diminishes as we rest in a more open, connected awareness.

What if non-dual teachings themselves trigger fear or confusion?

For some people, hearing that there is “no separate self” can initially feel destabilising or frightening, especially if there is a history of anxiety or dissociation. In such cases, it is helpful to proceed slowly, anchor in body-based safety practices, and treat fear as a sensation to be gently welcomed and felt rather than something to be argued with or suppressed, allowing understanding to deepen at a natural pace.

How do inner conflicts fit into the idea of “no other, no fear”?

Inner conflicts can be understood as different “parts” of the self, each with its own fears and needs, which can feel like internal “others” in opposition. Approaches such as Internal Family Systems, Voice Dialogue, and Genpo Roshi’s Big Mind process help bring these parts into conscious relationship and then into a wider field of awareness, so that the many inner voices are recognised as expressions of one underlying wholeness rather than warring fragments.

Can non-duality really help with everyday stress, like work or family pressure?

Yes, but usually in a gradual, integrated way. Non-duality does not remove deadlines or family responsibilities, but it can change the felt sense of who is carrying them, shifting from a contracted, isolated “me” to a more spacious awareness in which thoughts, emotions, and situations arise and pass. Combined with practical tools such as nervous system regulation, boundary-setting, and honest communication, this shift can make everyday stress more workable and less fear-driven.

Is the aim to get rid of fear completely?

Biologically, fear will always be available as a protective response, and it is necessary when genuine danger is present. The aim is not to eliminate functional fear but to end the unnecessary psychological fear and chronic anxiety that arise from misperception, so that fear becomes an occasional, appropriate signal rather than a constant inner climate.

Where can I start if I resonate with this but feel overwhelmed?

A gentle starting point is to combine simple daily practices with inquiry. This might include a few minutes of breath-focused awareness, body-based grounding, and then a quiet question such as “Who is aware of this experience?” without rushing for an intellectual answer. Over time, this builds both physiological safety and the taste of a wider awareness that is not defined by fear, supporting the “no fear” vision explored throughout the blog.

“Christ is the population of the world, and every object as well. There is no room for hypocrisy. Why use bitter soup for healing when sweet water is everywhere?”